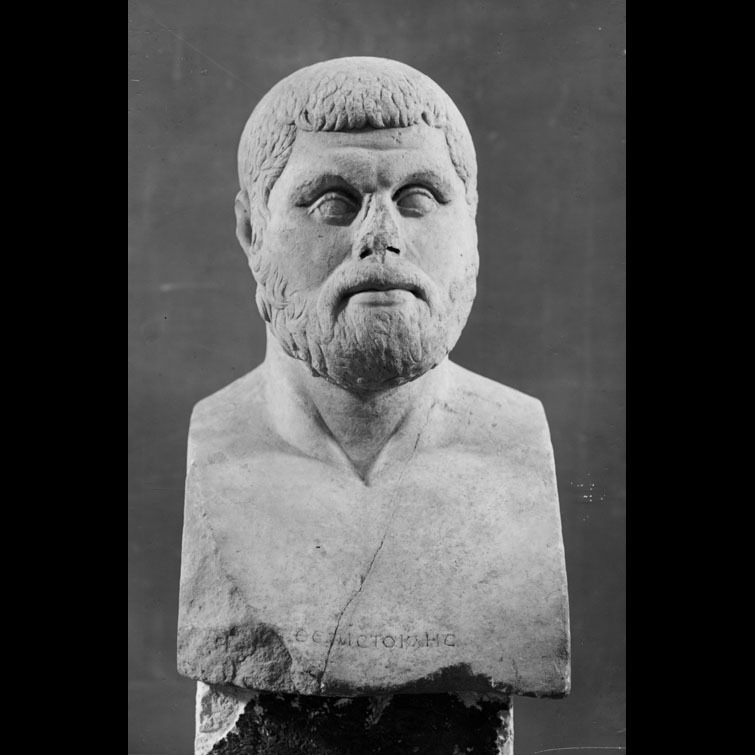

Bust of Themistokles

Title

Date

Artist or Workshop

Materials

Height of the work

Provenience

Current Location

Description and Significance

The ‘Bust of Themistokles’ depicts the head of a man and part of his upper chest, which is more specifically known as a herm, on the bottom of which rests a small Greek inscription of his name, ‘Themistokles’. In terms of facial features, the marble head consists of smooth, slightly rounded cheekbones, arched, well-defined eye-sockets, with eyelids and brow visible, and a deteriorated nose that shows signs of damage. The downward curve of his mouth forms a slightly protruding upper lip veiled by a thinly haired mustache, while the lower lip forms a strong horizontal line below. Combined with a square jaw that projects subtly forward and the creased brow and forehead, these elements convey what might be considered a stern expression, although the eyes look relatively blank, looking nowhere in particular. Below the head, a V-shape denotes the chest cavity under the thick neck, accentuating the overall naturalism. However, the hair, which stretches almost straight across the mid-forehead, curves diagonally at the sides of the head, extending to the chin and forming a beard filled with patterns of incised curls. The abrupt linear break of the hair at the forehead gives the appearance of a wig, with the repeated curved lines adding to this sense of stylization. This fusion of the natural and simplified implies idealization, although the features may be somewhat individualized.

Significance:

A Roman marble copy of a bronze Greek original, this bust, as confirmed by its inscription, portrays the Athenian politician and general, Themistokles, who lived from 528-460 B.C. Having come from a less aristocratic family than previous leaders, Themistokles purportedly rose to prominence on account of his strong will, through which he commanded the Athenian fleet and promoted Athens as a naval power prior to and during the Second-Persian War, in which he led Athens to victory at Salamis. In one sense, the sternness of the features, including the furrowed brow and solid jawline, suggests that the portrait could reflect his personality, described by the ancients Plutarch and Thucydides as “enterprising”, “brilliant”, and “shrewd”. This is the view of some scholars who believe that this particular bust is an anomaly in Early Classical portraiture, as it expresses a strong sense of individual character for the time, and may depart from the generic Greek types, such as the heroic, idealized figure. While the “true portrait” was supposedly not realized until later, this example from the Early Classical Period, marked by the distinct thrust of the head, thick neck and slightly forceful expression, may offer insights into the development of individualization in Greek portraiture. This considered, it does fall into the tradition of portraits of Greek military leaders produced during the time of the Persian Wars, meaning the level of individuation is debatable. Other contemporaneous sculptures such as the head of Philip of Macedon in Copenhagen, which bears a similar hairstyle and expression, may hint at shared attributes used by sculptors and slightly modified for individual traits. While the original full-figure bronze statue may have been displayed in Themistokles’ Temple of Artemis Aristoboule or his monument at Magnesia, as described by the ancients, this copy would have served the intellectual purposes of Roman clients, such as those in the House of Themistokles, the guild house which was named after this portrait when it was discovered in 1939. Aptly, in the view of one scholar, the sculpture’s bearing, with its coarse beard and cropped hair, is more akin to a Roman military emperor than a typical Greek commander, which may explain why some scholars view this piece as unique among Early-Classical sculpture.

References

Breckenridge, James D. "The Fifth Century: The Hero." Likeness: A Conceptual History of Ancient Portraiture. Evanston: Northwestern U, 1968. 89-90. Print.

Hanson, Victor Davis. "Holy Salamis (September 480 B.C.)." The Savior Generals: How Five Great Commanders Saved Wars That Were Lost - From Ancient Greece to Iraq. 1st ed. N.p.: Bloomsbury, 2013. 34. Print.

Phang, Sara E., Douglas Kelly, and Peter Londey. "Themistocles (ca. 528-460)." Conflict in Ancient Greece and Rome. The Definitive Political, Social, and Military Encyclopedia. 3 Vols. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 2017. 546-47. Print.

http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/artifact?name=Ostia+Themistokles&object=Sculpture

http://www.ostia-antica.org/vmuseum/marble_2.htm

https://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/sculpture/styles/portraiture.htm

http://www.stoa.org/projects/demos/article_portraits?page=all

Contributor

Citation

Item Relations

This item has no relations.