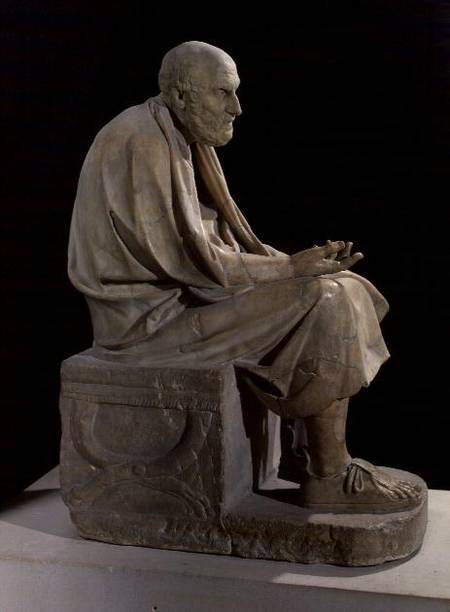

Seated Chrysippos

Title

Seated Chrysippos

Date

Hellenistic original, 250 BCE-50 CE; copy, 2nd century CE

Artist or Workshop

Copy after Euboulides (Greek sculptor)

Materials

Marble

Height of the work

Est. 170 cm tall (based on known height of head = 36 cm tall)

Provenience

Athens, Greece

Current Location

Head: the British Museum, London, United Kingdom

Body: the Louvre, Paris, France

Body: the Louvre, Paris, France

Description and Significance

Description:

The portrait statue of Chrysippus depicts the Stoic philosopher in a seated position, his back bent over with age. He sits upon a stone block, tucking his feeble legs closer to his body and pulling his himation tighter around his bare shoulders and sagging chest. His left hand is balled up into a fist on his lap, which also holds the cloak tightly underneath. His right hand is free, the fingers bent and extending towards the viewer to indicate numeration. His head is projecting forward towards an imaginary opponent, and his face portrays that of a man in the middle of a dispute. More specifically, the head is exquisitely detailed, with sunken eyes, furrowed brows, and several sharp creases at the top of the nose. The dotage prevalent in the Chrysippus statue continues with the figure's heavily lined eyes and sagging cheeks. His beard is composed of unruly tufts that extend unevenly in different directions. His head is balding and appears dome-like in shape due to his close-cropped hair style and boney structure.

Significance:

The portrait statue of Chrysippus has a number of features that help define the philosophic image of its deceased counterpart: the beard, furrowed brows, tightly drawn himation, and seated posture all hearken back to the philosopher image of the Hellenistic period. His sagging body and contemplative expression might have been intended by Euboulides to emphasize the portrait as resolutely philosophic. This blatant disregard for the philosopher’s temporal body suggests that Chrysippus favored intellectual prowess over physical fitness. However, these few elements alone would not have been enough to connote Chrysippus’ image in antiquity. More specifically, individualizing features like the gesture of the right hand and energetic thrust of the head are explicit characteristics of Chrysippus. Chrysippus was more than just an aggressive speaker; he was a great Stoic dialectician who represented argumentation and logical deduction in stoicism (one of the main philosophical "schools" in Athens). In this case, his extended right hand represents a particular form of thinking, the fingers perhaps ticking off the order of his winning points. His powerfully expressive face is contrasted with his particularly frail body, which emphasizes how the power of his spirit triumphs over the weakness of his body. These elements precisely communicate not only the portrait subject’s social standing in society, but also his individualizing features as a philosopher in antiquity.

It is of some significance to note that the statue is also a combination of two separate sculptures; however, art historians are fairly certain that they have the correct arrangement because Cicero specifically refers to these individualizing features formerly stated. Another part of what makes the statue of Chrysippus a significant part of history is the change from the “formal” and renowned stance to a more personal stance depicting a man (in this case, a philosopher) frozen in the midst of doing something he was once celebrated throughout antiquity for. In other words, the viewer gets a rather intimate depiction of an individual as opposed to other Hellenistic portraiture.

The portrait statue of Chrysippus depicts the Stoic philosopher in a seated position, his back bent over with age. He sits upon a stone block, tucking his feeble legs closer to his body and pulling his himation tighter around his bare shoulders and sagging chest. His left hand is balled up into a fist on his lap, which also holds the cloak tightly underneath. His right hand is free, the fingers bent and extending towards the viewer to indicate numeration. His head is projecting forward towards an imaginary opponent, and his face portrays that of a man in the middle of a dispute. More specifically, the head is exquisitely detailed, with sunken eyes, furrowed brows, and several sharp creases at the top of the nose. The dotage prevalent in the Chrysippus statue continues with the figure's heavily lined eyes and sagging cheeks. His beard is composed of unruly tufts that extend unevenly in different directions. His head is balding and appears dome-like in shape due to his close-cropped hair style and boney structure.

Significance:

The portrait statue of Chrysippus has a number of features that help define the philosophic image of its deceased counterpart: the beard, furrowed brows, tightly drawn himation, and seated posture all hearken back to the philosopher image of the Hellenistic period. His sagging body and contemplative expression might have been intended by Euboulides to emphasize the portrait as resolutely philosophic. This blatant disregard for the philosopher’s temporal body suggests that Chrysippus favored intellectual prowess over physical fitness. However, these few elements alone would not have been enough to connote Chrysippus’ image in antiquity. More specifically, individualizing features like the gesture of the right hand and energetic thrust of the head are explicit characteristics of Chrysippus. Chrysippus was more than just an aggressive speaker; he was a great Stoic dialectician who represented argumentation and logical deduction in stoicism (one of the main philosophical "schools" in Athens). In this case, his extended right hand represents a particular form of thinking, the fingers perhaps ticking off the order of his winning points. His powerfully expressive face is contrasted with his particularly frail body, which emphasizes how the power of his spirit triumphs over the weakness of his body. These elements precisely communicate not only the portrait subject’s social standing in society, but also his individualizing features as a philosopher in antiquity.

It is of some significance to note that the statue is also a combination of two separate sculptures; however, art historians are fairly certain that they have the correct arrangement because Cicero specifically refers to these individualizing features formerly stated. Another part of what makes the statue of Chrysippus a significant part of history is the change from the “formal” and renowned stance to a more personal stance depicting a man (in this case, a philosopher) frozen in the midst of doing something he was once celebrated throughout antiquity for. In other words, the viewer gets a rather intimate depiction of an individual as opposed to other Hellenistic portraiture.

References

The British Museum Website: http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=460098&partId=1

Dillon, Sheila. “Greek Portraits in Practice.” Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 114-115. Print.

Harvard University Library Website: http://via.lib.harvard.edu/via/deliver/deepcontentItem?recordId=olvwork295837%2CDIV.LIB.FACULTY%3A828683

Hekler, Antal. Greek & Roman Portraits. Place of Publication Not Identified: Hardpress, 2012. 22. Google Books. Web.

Pollitt, J.J. “Personality and Psychology in Portraiture.” Art in the Hellenistic Age.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 2009. 69. Print.

Dillon, Sheila. “Greek Portraits in Practice.” Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012. 114-115. Print.

Harvard University Library Website: http://via.lib.harvard.edu/via/deliver/deepcontentItem?recordId=olvwork295837%2CDIV.LIB.FACULTY%3A828683

Hekler, Antal. Greek & Roman Portraits. Place of Publication Not Identified: Hardpress, 2012. 22. Google Books. Web.

Pollitt, J.J. “Personality and Psychology in Portraiture.” Art in the Hellenistic Age.Cambridge: CambridgeUniversity Press, 2009. 69. Print.

Richter, Gisela M. A. “Criteria for the Identification.” Greek Portraits II: To What Extent Were They Faithful Likenesses? Bruxelles: Latomus, 1959. 34. Print.

Zanker, Paul, and H. A. Shapiro. The Mask of Socrates: The Image of the Intellectual in Antiquity. Berkeley, CA: CaliforniaUniversity Press, 1996. Print.

Contributor

Ryan Tetter

Citation

Copy after Euboulides (Greek sculptor) , “Seated Chrysippos,” Digital Portrait "Basket" - ARTH488A "Ancient Mediterranean Portraiture", accessed June 6, 2025, http://classicalchopped.artinterp.org/omeka/items/show/26.

Item Relations

This item has no relations.